Tight deadline? Here’s how to compose economically

Author: Blogger in Residence, Anna Disley-Simpson

We’ve all done it. It’s a shared human experience. In a world where we’re all busy and spread so thinly, a deadline can creep up on you like a detestable lurking goblin. I’ve been in this particular black hole for the month of January, as I’ve had just over a month to write a 10 minute piece for choir and full orchestra. Whilst I’ve largely relished the process, I’ve definitely learnt some things. Here’s my advice on composing a piece in a shorter-than-ideal space of time.

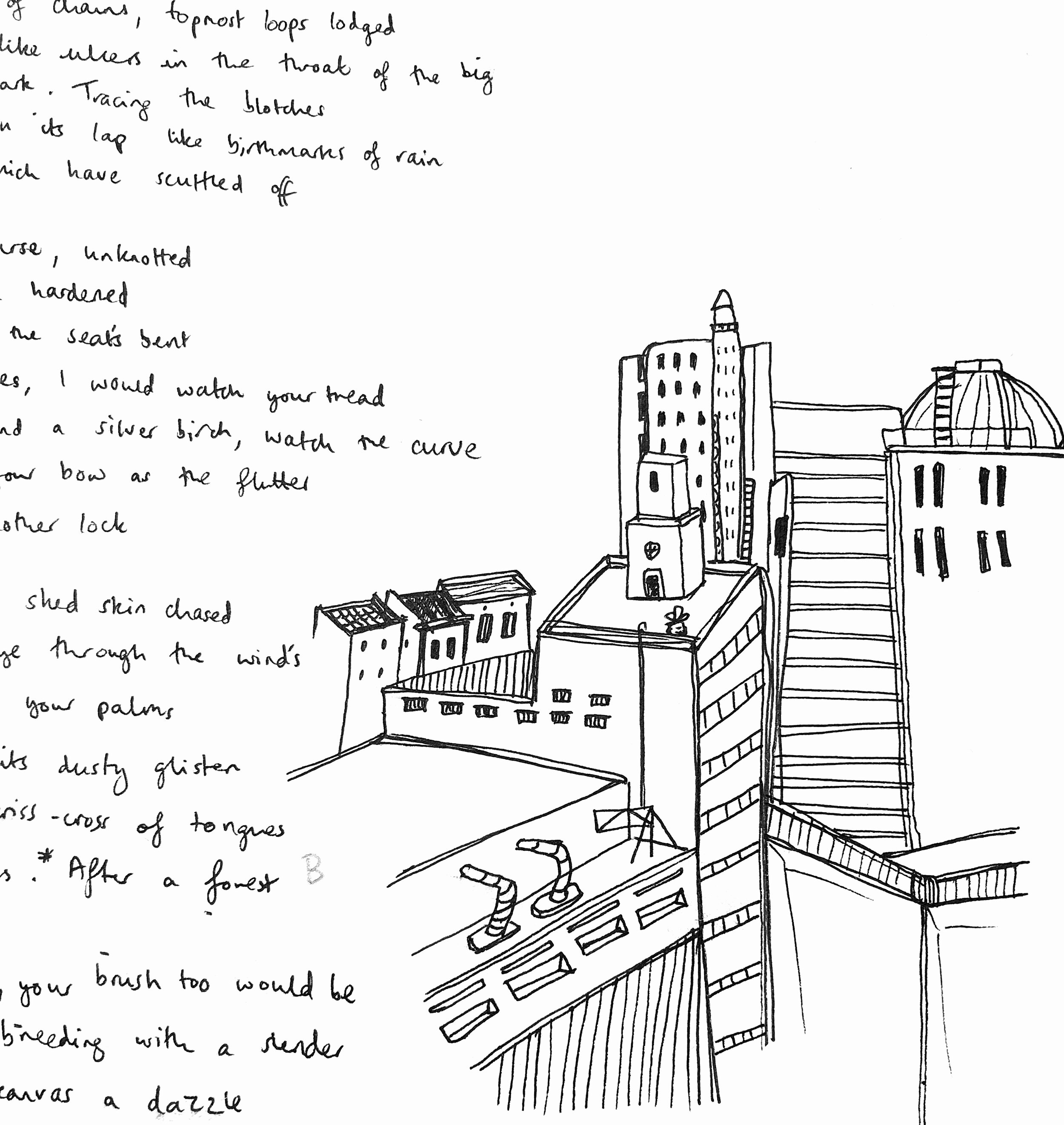

Plan out your piece like you’d plan out an essay. Drawings, sketches, diagrams, words, rhythmic cells, musical scales or vague harmonic language are all things that I will start with before writing a single bar. I see it as a mind-map in which to expel all my ideas which can then be deciphered and structured later on. For me it’s infinitely valuable to have this type of plan and it’s something which I will refer to throughout the realisation of the piece, like I’m going back to cherry-pick elements in order to assemble a bigger musical collage. Sketching out a timeline in order to pinpoint musical events and build a structure can also be very helpful.

Extract from the sketches for my new piece for the London Oriana Choir and the Meridian Sinfonia, ‘Picture Frame’. Premiered on Friday 13th March 2020 at St. Giles’ Cripplegate, London.

Repetition is your friend. I recommend this not as a means of cutting corners per se, rather to utilise it to the artistic and/or structural advantage of the piece you are making. Repetition is undeniably integral to all music (even if that means a rejection of the notion, such as a serialist piece using a tone row where no pitch is repeated). We even listen to pieces of music repetitively, often hundreds of times over, which is something we don’t do nearly as much with speech (when was the last time you listened to a podcast or an audiobook more than once?).

We as humans love to hear musical ideas many times; rhythms, melodies, a recognisable chord. It’s what makes music memorable, and often helps to establish its form. Go too far the other way though, and your piece may start to toe the line of sounding lazy or boring. Perhaps think of some creative ways in which to repeat certain ideas. Could you vary each iteration of the idea? Change the voicing or the instrumentation? Flip it upside down?

Remember you don’t have to use all the instruments or voices all of the time. I’ve mentioned rhythm, melody, and harmony a few times, but textural and dynamic changes can often be the most distinctive and effective. Our instinct can be to make constant use of all our available forces, but what happens when the bulk of the material dissipates? Perhaps a wind quintet could emerge from a dense orchestral texture, or a single solo voice can carry a melodic line over a wash of choral sound that occurs in intervallic waves.

Revisit old ideas. Think how they can be transferred and transformed in a new context. I find that ideas from previous pieces often get lost along the way and don’t make the final cut. However small, these discarded gems will frequently end up being integral to future works.

Know your Sibelius shortcuts. (Or Finale, or MuseScore, or Dorico if you’re edgy.) Knowing how the software works inside out will save you literally hours of work. Alternatively, reject notation altogether in favour of a text score (more on these in my next post), or even compile a piece that can entirely be taught by ear. The choice is yours.

In general, it’s a good time to favour ‘big brush strokes and broad textures’. (Anna Meredith’s pragmatic words of wisdom given in an old (but gold) interview here) Whether this approach appeals to you or not, working in a non-precious, playful way is bound to result in some very exciting music. A simple yet bold idea can often be the catalyst for some of the best works of art around.

See it as an exercise. A learning experience. A chance to grow as a musician. Don’t stress. Writing music is (meant to be) fun.

Written by Anna Disley-Simpson